Is It Really a Housing Shortage? Or Is It a Livability Problem?

Let’s get real about what we’re building in Toronto.

It’s not that we aren’t building enough housing units – it’s that we’re building the wrong kind of housing.

Take a look through almost any new development brochure and you’ll see the same pattern: 450–550 sq. ft. studios and one-bedroom units, stacked floor after floor. What’s missing are family-sized condos, livable two- and three-bedroom suites, and layouts that actually support long-term living.

This isn’t accidental.

It’s the result of how the system is structured – and more specifically, how development charges (DCs) and incentives distort what gets built.

What I Learned Working Inside Toronto Condo Development Teams

Before focusing full-time on residential resale, I worked in-house with Toronto condo developers. I sat in the meetings where floorplan mixes were debated, revenue targets were stress-tested, and projects were pushed to meet the all-important 70% pre-sale threshold required by lenders before construction could begin.

Here’s what I witnessed first-hand:

End users rarely buy three-bedroom condos four to six years in advance. The buyer pool is simply too small. Families looking for a three-bedroom typically want to move within months – not in 2029.

As pre-sale timelines have stretched longer, developers have been forced to prioritize what sells fast, not what lives well. That means loading projects with smaller units that investors are more willing to commit to early.

Even where planning guidelines require a certain unit mix, overall suite sizes have continued to shrink. Compare a one-bedroom built in 2015 to one built in 2025: the cost per square foot has risen dramatically, leaving developers under pressure to reduce square footage just to make projects pencil.

And then comes the real kicker.

Development Charges Are Killing Livability – Not Developers

If the City of Toronto genuinely wants to incentivize livable, end-user-focused housing, it needs to acknowledge a simple truth:

Incentives drive outcomes.

Right now, the economics discourage larger units. Higher DCs applied uniformly across unit types make family-sized suites disproportionately expensive to build, even though they’re the very product the city claims to need more of.

If we want different housing, we need different math.

My Proposal: Flip the DC Model

If Toronto is serious about promoting livable housing, it’s time to flip the incentive structure.

- ✅ Higher DCs on micro-units and studios

These are primarily investor products and should be treated as such. - ⚖️ Mid-range DCs on two-bedroom units

These serve couples, small families, and some investors. - 🏡 Lowest DCs on three-bedroom and family-sized units

This is the housing product Toronto is missing most – and currently being taxed out of existence.

This approach doesn’t eliminate development charges.

It simply realigns them to reward the kind of housing people can actually live in.

Why “More Supply” Isn’t the Whole Solution

There’s a persistent narrative – especially among policymakers – that the housing crisis can be solved with “more supply.”

But supply of what?

If we continue to flood the city with investor-driven micro-units that don’t work for families, downsizers, or even many professionals, we aren’t solving a housing problem. We’re creating new ones:

- higher vacancy in small units

- unlivable spaces

- poor long-term city planning

Quantity without livability is not a solution.

Mayor Olivia Chow’s Multiplex DC Relief: A Step in the Right Direction

Recently, Mayor Olivia Chow announced development charge relief for multiplex projects. This was a meaningful and much-needed move – and it shows there is political will to rethink the system.

But it raises an important question: why stop there?

If affordability and livability are the goals, why not rework DCs for vertical housing as well? Especially when the alternative is watching Toronto become a grid of investor shoeboxes that don’t meet the needs of the people who actually live here.

Why Condo Construction Is Still Stalled: The Missing Buyer Pool

There’s another major factor keeping Toronto condo projects in a holding pattern.

Foreign investment has effectively paused.

Historically, foreign buyers played a significant role in Toronto’s pre-construction market. Not because they were end users, but because they were often the only buyer group willing to commit capital at scale, years in advance, allowing projects to hit pre-sale thresholds and secure construction financing.

Today, that buyer pool is largely absent. Foreign buyer restrictions, higher interest rates, currency risk, and geopolitical uncertainty have pushed international capital to the sidelines.

End users haven’t replaced that demand. Families and downsizers don’t buy homes they won’t live in for years. Investors, meanwhile, are facing thinner margins, higher carrying costs, and more uncertainty.

The result is predictable: projects stall, supply doesn’t materialize, and developers are blamed – even though the economics no longer support construction under current rules.

Until incentives are realigned and a viable early-stage buyer pool returns, much of Toronto’s condo pipeline will remain frozen.

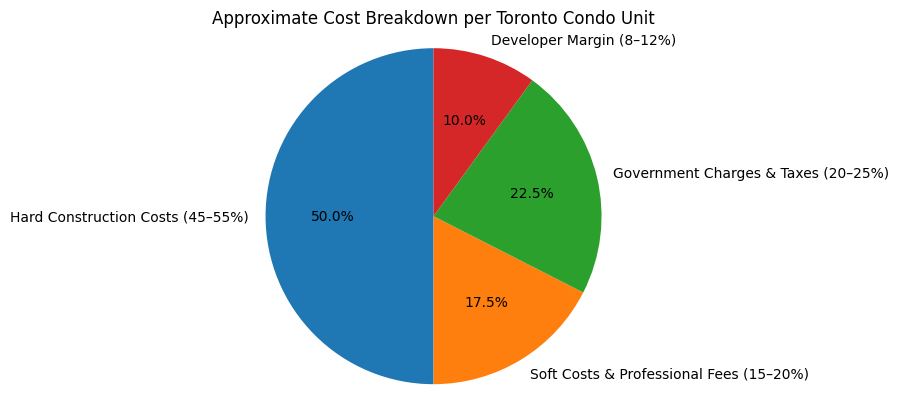

Where the Money Actually Goes: A Toronto Condo Cost Breakdown

To understand why certain housing types aren’t being built, it helps to look at where each dollar actually goes in a typical Toronto condo unit.

Below is an approximate cost breakdown, based on City of Toronto development charge studies, industry financial disclosures, UDI/BILD construction data, CMHC feasibility models, and public developer reporting. Percentages vary by project, but the ranges are consistent.

Approximate Cost Breakdown per Toronto Condo Unit

- Hard Construction Costs: 45–55%

Materials, labour, site work, mechanical and electrical systems. These costs have risen sharply since 2019. - Soft Costs & Professional Fees: 15–20%

Architecture, engineering, planning, consultants, marketing, legal, financing, and project management. - Government Charges & Taxes: 20–25%

Development charges, parkland dedication, community benefits charges, permits, and net HST. - Developer Margin (Risk-Adjusted): 8–12%

This is not guaranteed profit. It is realized years later and fully exposed to market, financing, and construction risk. In many projects today, this margin is compressed to the low end – or disappears entirely.

In many Toronto developments, the City collects more per unit than the developer ultimately earns.

Final Thoughts: Want Livable Housing? Change the Incentives

Toronto’s housing crisis isn’t just about affordability – it’s about a fundamental product-market mismatch.

We’ve created a system that taxes livable housing out of existence, discourages family-sized units, and relies on investor capital that no longer shows up.

As someone who has worked inside development teams and now helps people buy and sell homes in this city, I see both sides clearly.

It’s time to stop blaming developers and start questioning the incentives we’ve put in place. Because incentives drive design. And right now, we’re incentivizing the wrong thing.

What Do You Think?

Would you support a flipped development charge model that rewards family-friendly housing and discourages investor micro-units?

Share your thoughts in the comments – or reach out if you’re an end user trying to find livable space in a city that makes it increasingly difficult.